Adam Tooze on the schizophrenic South African experience

"the fear, that haunts, South African society — of total breakdown is, is traumatic..."

I’m an out-of-the-closet Tooze-bro. So imagine my excitement when South Africa’s economy was the subject of his latest Foreign Policy podcast. It did not disappoint, although I felt Tooze held back a bit. Until the end, when his gloomy and, in my opinion, quite correct assessment landed.

Here is an excerpt from that end, with Tooze talking about Eskom, South Africa’s giant state energy company:

That has been an absolute crisis of corporate governance with the CEO, Andre de Ruyter. Essentially resigning from his position on the threats from within the organization, that there's credible reason to believe that there was a poisoning attempt, that an assassination attempt was made against him, by the mafia groups that operate within Eskom. So there were powerful, organized crime syndicates connected to the trade union and the ANC, operating in the major coal regions of South Africa who see themselves as having a vested interest in this, in this malfunctioning giant.

This goes from, you know, large-scale resistance to green energy as an option for the future, down to criminal gangs that systematically rob coal trains, replace the coal, the good coal with bad coal, or even scrap metal, which then gets fed into the furnaces, which then sabotages and blows up the power stations. The fear here, and it's a very real terror, is of what would happen in a society as unequal and as violent a society, with as much simmering resentment as there is in South Africa, if there were to be a prolonged and serious power shortage?

And we have seen rioting in recent years, which was taken on the scale of civil war conditions. And while I was there, the insurance companies in South Africa actually publicly declared that we're there to be a power outage, they were not committing themselves in advance to honoring insurance contracts on private property in the event of large-scale civil disturbance.

So that is the kind of level at which the conversation is carried on in South Africa, all of this within a society, which unless you look below the surface, You might not think was really shaking. I mean, it's, it's a remarkably schizophrenic experience being there because it's a highly developed society with great internet.

And if you live in the more prosperous parts, You know, you have no sense at all of being on the edge of a precipice or, you know, on the edge of a volcano. But the fear, that haunts, South African society — of total breakdown is, is traumatic, it really is.

It is this breakdown of a modern state, albeit a very particular one, that partly fuels my fascination with states. That, and people in the West taking the states they live in for granted. This is partly the reason I started this newsletter.

Adam Tooze’s podcast, called Ones and Tooze, is where he uses a few data points as a way to illuminate a subject. But like most commentators on South Africa, even someone with Tooze’s analytical ability seems best at describing the tragedy, rather than explaining how we got there.

Some counter-intuitive graphs on South Africa

Here is a set of numbers, graphs, in fact, that, in my opinion, should be included for a discussion on South Africa because they are so counter-intuitive to existing narratives. And I think unpicking and explaining these graphs will go some way (though not all) to burn away the mist that envelops the countries’ sad trajectory.

All these graphs are from the World Incomes Database, in whose creation Thomas Piketty had a hand. The first shows the share of national income that went to South Africa’s top 1% of earners. During WW2, this bracket earned its most significant share of national wealth. From then to 1993, their share fell. But it’s right back up now.

The second shows the share of national income that went to the top 10%. The top 10% of earners also took the lowest share of national wealth in 1993. Today they are as high as ever.

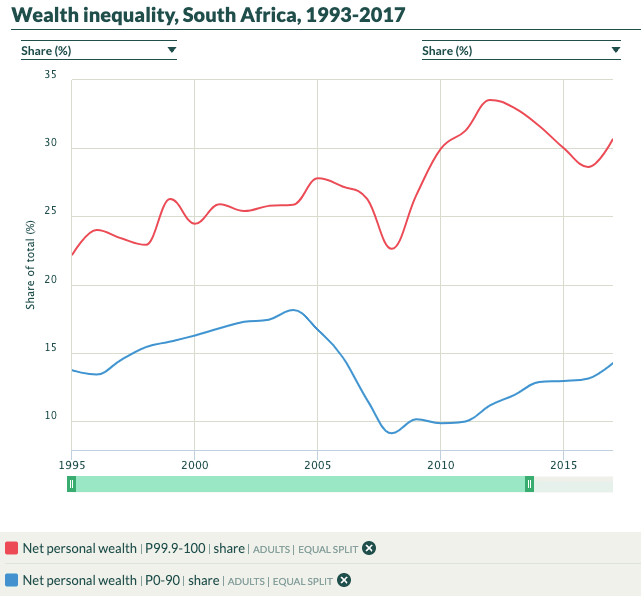

The last, which only starts in 1995, unfortunately, shows the share of the wealth that went to the top 0.1% and bottom 90%. The 0.1% bracket’s wealth has only increased in the last three decades. The bottom 90% have about the same share of wealth as they had in 1995, after a low round 2008.

Well argued case. Good one.

Good article. Thank you for the write up