More annoying, and more of it - online advertising in the future (links 4)

And the intellectual tide against an active state is turning, we are under-hyping AI

In this week’s newsletter: the campaign for privacy will have unintended consequences, more and more annoying ads. The big active state is making a comeback, partly because of changes in the intellectual climate, and we are in danger of underestimating AI.

You will begin to see more annoying ads as a result of Apple's App Tracking Transparency (ATT). And according to The New York Times, anecdotally at least, that is what is happening.

Other less obvious unintended consequences have been discussed by me a few times: how ATT will lead to online consolidation, for example.

Yet the New York Times still fails to mention this: targeted ads not only mean more relevant ads but also mean fewer ads and lower costs for the advertiser.

Additionally, targeted ads encourage and allow smaller ad campaigns, which is advantageous to startups and small businesses, especially for niche products. Fast-moving consumer goods, like toothpaste and petrol, tend to have more undifferentiated consumers. So the large companies that provide these products don’t care as much about targeting.

All this is because of how ad platforms work (simplifying here for the sake of brevity). There cannot be too many ads on platforms, or users will stop using them. As a result, they cap the frequency per user over a period of time, which means there is a limited amount of ad inventory available.

Platforms display ads until an advertiser's goal is reached (clicks or conversions). The price is determined by how many ads need to be shown until this happens. With very targeted ads, few need to be shown.

Due to Apple's ATT and soon-to-be legal restrictions in Europe, targeting is now more difficult, so expect not only fewer relevant ads, but also more. You can also expect costs to rise, particularly for small businesses, charities, and start-ups.

But what about the scourge of “surveillance” capitalism? In my opinion, the moral panic over tracking, ads, and privacy is misplaced, and the issue of privacy can be effectively addressed with the right regulation making a distinction between what amounts to three separate issues: security, privacy and nuisance.

In related (told-you-so) news:

As I predicted - Elon Musk’s plans to fund Twitter via premium payments instead of ads is not working out.

(Musk’s Twitter Has Just 180,000 U.S. Subscribers.)

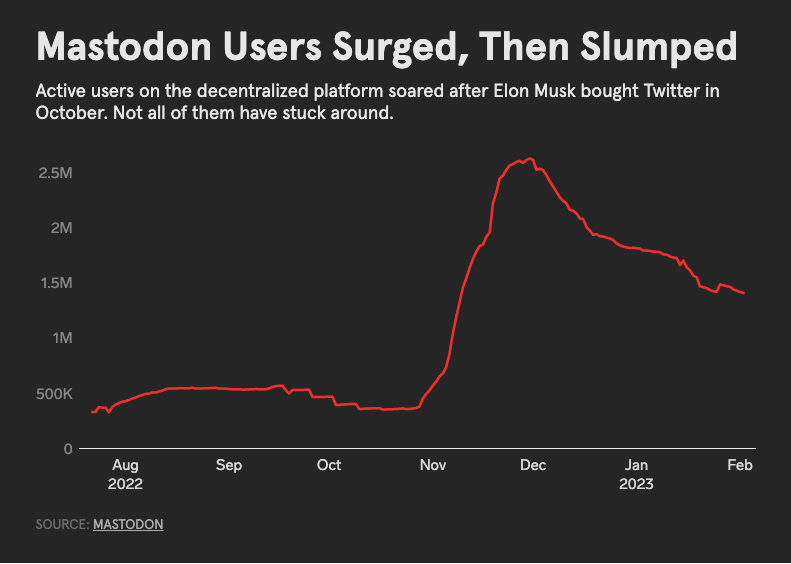

And… As I predicted - Mastodon will have trouble replacing Twitter.

(Mastodon’s daily active monthly user count dropped to 1.4 million by late January from 2.5 million in December.)

An active state: The intellectual tide has turned

There are times when the intellectual ground beneath our feet shifts dramatically without much fuss. The idea of governments doing industrial policy is hot right now, as I mentioned in my last newsletter. Until very recently, that was anathema to much of western thinking. In its state aid rules, for example, the EU has prohibitions against this written in stone, which are now being overridden by "temporary" measures.

In this vein, Martin Wolf sent tongues wagging with his answer to a question at a talk this week that he sounded “Marxist”. Wolf is the chief economics writer for the Financial Times, a position he has held for decades. A highly respected economist, and with meticulously argued essays, he criticized the Tory government's austerity policies, as well as much of Europe's response to the financial crisis. Wolf argued - correctly, as it turned out - that cutting government spending when businesses are cut spending too would not reduce government debt or lead to robust growth, but the opposite.

Wolf has a book out, which he claims will be his last. He started writing it after Trump came to power and Brexit happened. The reasons for these things happening, he says, are long-term - the erosion of welfare states since the 1970s - and more recent - the financial crisis. Despite its obviousness, I have yet to see a writer explicitly link the rise of populism and the financial crisis.

The book is about his concern about “democratic capitalism”. A system he believes in but which he feels is now under profound threat. It is a system that he feels is particularly vulnerable to unscrupulous populists without significant growth and lower levels of inequality in our societies. A measure of how the ground has shifted is that The Financial Times’s editorial board famously supported austerity in the early 2010s, and Wolf was a lone voice. But now they agree with him. And even the mouthpiece of free trade and unfettered markets, the Economist, their Europe editor, tweeted this, this week about Germany’s rail network grinding to a halt:

In related news:

The UK may not have an industrial strategy, but it is planning on launching something akin to the US’s DARPA, the government research agency that launched the internet. It’s called Aria.

The rampant “statism” that we now see in China (which has been a primary theme of Chinese political economy since 1912) is a direct reaction to the perceived failures of the Qing dynasty, which undertaxed the peasants and was to weak to compete with other states in the modern world.

Underhyping AI

A new study warns of a tendency by AI researchers to understate successes and warns that this may make it harder to mitigate harm. Just this week, one example.

The New Yorker ran an article to demystify AI, using a metaphor to do so. Large language models (LLMs) work like blurry JPEGs it was said, implying they do memorizing and rephrasing what they have learned.

This thread counters that, arguing that existing science already shows LLMs are more powerful than that: LLMs can learn generalizable strategies that perform well on truly novel test examples on which they were not trained.

In related news:

Not a cheap worker replacement. AI use will cost a lot more than we think?