Why the marketplace of ideas failed online

Letting everyone talk to everyone does not lead to more rational discussion

"WHEN we use a network, the most important asset we get is access to one another," wrote Clay Shirky in his book, Here comes everybody, a book about the internet and social media in 2008. Back then, most people believed the internet would do more than just innovate — it would free ordinary people to connect, express themselves, and even spread democracy around the world.

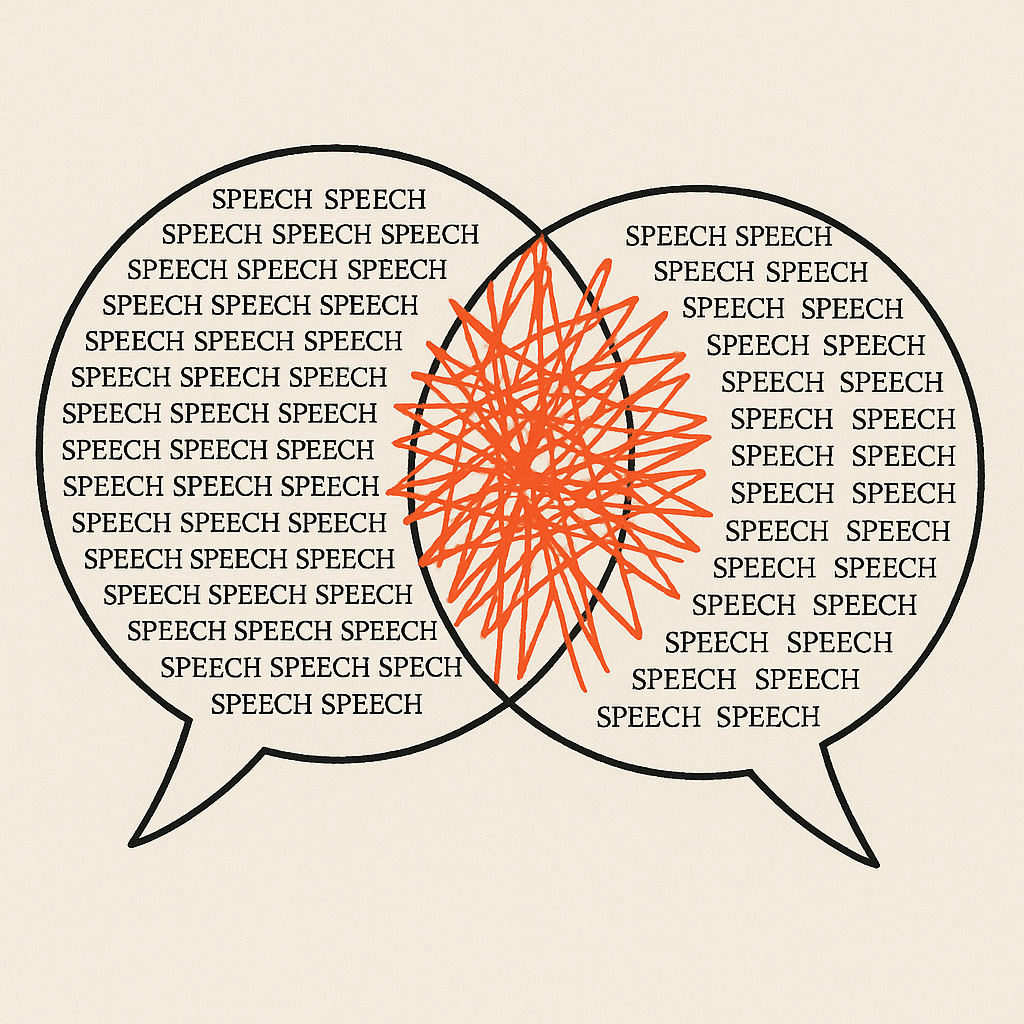

The thinking was simple: bad speech would be drowned out by good speech, and from all this conversation, truth would emerge. This faith in the power of free-flowing ideas runs deep in Western thinking. Philosophers from Milton to Locke to Voltaire all championed it.

John Stuart Mill argued in On Liberty that freedom of speech and debate are essential because they allow truth to emerge from the clash of opinions. Something many later compared to a marketplace. For Mill, open discussion prevents dogma, corrects error, and sharpens understanding — making progress and healthy democracy possible.

Fast forward to today: democracy is retreating worldwide and conflict is rising. Within democracies, division has become so bitter it's eating away at the fabric of society. We need to face an uncomfortable possibility: What if letting everybody speak to everybody doesn't bring enlightenment? What if it actually spreads division and chaos so effectively that it endangers democracy itself?

Within democracies, division has become so bitter it's eating away at the fabric of society. We need to face an uncomfortable possibility: What if letting everybody speak to everybody doesn't bring enlightenment? What if it actually spreads division and chaos so effectively that it endangers democracy itself?

The Old Media World and Its Critics

Before the internet, the media world of democracies had plenty of critics. To be a publisher, you needed serious money. You had to buy massive printing presses, build distribution networks, or own a TV station. You needed specialized staff and advertising departments — all requiring substantial capital.

Noam Chomsky captured this critique well in Manufacturing Consent. He argued that these big media corporations had built-in biases and carefully controlled what topics were up for discussion. Since they depended on advertising revenue, they tended to avoid rocking the boat. (Elon Musk recently discovered firsthand how advertisers can constrain what you say.)

The result? Media that pushed society toward safe, middle-of-the-road consensus. The left especially disliked this system, seeing how commercial interests prevented serious discussions about creating a more equal society.

Then came the internet and social media. The left hoped these new tools would bypass corporate media's manufactured consensus. As the saying goes: be careful what you wish for.

The left hoped these new tools would bypass corporate media's manufactured consensus. As the saying goes: be careful what you wish for.

The Filter Bubble: Only Half Right

Eli Pariser was among the first to sense something was off with online media. In The Filter Bubble (2011), he warned that online, we tend to connect with people who already agree with us. Algorithms make this worse by showing us content we'll like, shielding us from challenging viewpoints.

This theory felt right because it fit our existing beliefs about the marketplace of ideas: if only we were exposed to diverse opinions, we'd debate our way to enlightenment.

But recent research shows Pariser’s Filter Bubble Theory was only half right. Yes, we prefer our own tribe and befriend like-minded people. But here's the twist: even on platforms without engagement-based algorithms (like Mastodon's simple chronological feed*), we actually pay more attention to posts from people we disagree with — especially when they say something we find morally outrageous. We notice it more, read it more, share it more, and comment on it more than other content.

But recent research shows Pariser’s Filter Bubble Theory was only half right. Yes, we prefer our own tribe and befriend like-minded people. But here's the twist: even on platforms without engagement-based algorithms (like Mastodon's simple chronological feed), we actually pay more attention to posts from people we disagree with — especially when they say something we find morally outrageous.

Why We're Wired for Outrage

Humans evolved as a highly social species. We developed psychological traits that helped us maintain tight-knit groups — a crucial survival advantage in a dangerous world. Morality itself evolved to help us cooperate and manage these small social groups. We're literally hardwired to notice and react to people breaking the rules of cooperation above almost everything else. In small groups, this instinct helps maintain order.

So the problem isn't that we don't see opposing viewpoints — it's that we see too many of them, and only the most extreme examples.

Research shows that compared to offline life, we're far more likely to hear about someone doing something "immoral" online than through print, radio, and TV combined. This constant exposure to others' wrongdoing breeds contempt. And algorithms designed to maximize engagement only amplify our natural instincts.

So the problem isn't that we don't see opposing viewpoints — it's that we see too many of them, and only the most extreme examples.

The Extremism Illusion

Making matters worse, we assume these extreme examples represent what the other side actually believes and does. We forget that people are motivated by status-seeking, and a small minority gain status by saying outrageous things that trigger our instincts — things that algorithms then boost to millions.

Online, your follower count is the clearest status signal. It also can determine your reach — how many people see your messages. The fastest way to build followers? Post extreme, emotional content. But in reality, only a small number of people generate most of this attention-grabbing content.

The Problem with Online Punishment

Another evolved trait compounds the problem: what researchers call "third-party punishment." This is when we take action to discipline someone who broke the rules, even at a cost to ourselves. You can see it in children — like when a child gives up their spot on the slide to stop another child who cut in line.

We're especially likely to punish rule-breakers when others are watching, probably because it shows we're reliable group members. Online, we always have an audience, and punishing wrongdoers maximizes our chances of attention and status within our group.

But here's the catch: before the internet, this punishment was costly. It only made evolutionary sense when you had to live day-to-day with the people you were disciplining — not when they live across town, across the country, or across the planet.

We're especially likely to punish rule-breakers when others are watching, probably because it shows we're reliable group members. Online, we always have an audience, and punishing wrongdoers maximizes our chances of attention and status within our group.

Technology Is Indifferent

Technology changes how we interact, but it doesn't care about the outcome. The printing press, with its one-to-many communication, is linked with the Enlightenment and the birth of nation-states. We got lucky. Now were out of it: digital technology's many-to-many megaphone might be putting that entire project in reverse.

The promise of everyone speaking to everyone hasn't delivered enlightenment. If there ever was a marketplace of ideas online, it is an example of market failure.

Instead, the internet may have given us something our evolved psychology was never equipped to handle: constant exposure to the worst of human behavior, amplified by algorithms and stripped of the natural constraints that once kept our punitive instincts in check. It is pulling democratic societies apart.

* People love to criticise engagement boosting algorithms, and though they make these issues worse, platforms with no algorithms like Mastodon face the same baseline issue.

This piece originally appeared in Vrye Weekblad.